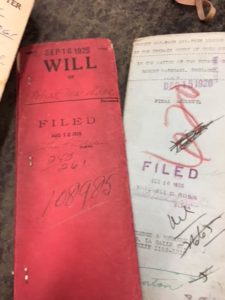

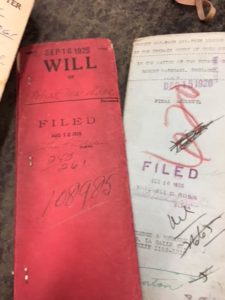

I sat down at a table in the Archives office with a mix of excitement and trepidation. There were three files in front of me: two thick (folded) files each labelled “Robert Marshall” and one flat, fairly thin file labelled “Laurence Christie.”

I sat down at a table in the Archives office with a mix of excitement and trepidation. There were three files in front of me: two thick (folded) files each labelled “Robert Marshall” and one flat, fairly thin file labelled “Laurence Christie.”

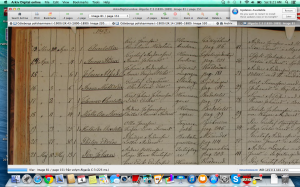

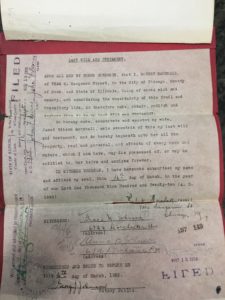

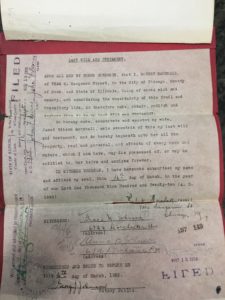

I opened the thick file and immediately could tell that it contained the will and probate records of my grandfather. I didn’t expect an actual will, but there it was, a thin piece of paper covered in type, signed and witnessed. Its contents was unremarkable: He assigned his wife executrix of his estate and bequeathed unto her all the property, real and personal, and effects….” It was dated 16 March 1922.

Although it begins includes the customary phrase “considering the uncertainty of this frail and transitory life,” I’m sure he had no idea it would be needed just three years later.

In August, my grandmother testified in open court verifying his death, her relationship to him, and the birth of his children. The will was proved in September and Janet Bitcon Marshall was was named executrix.

In October, she gave birth to David Marshall, my dad. On November 24, Laurence Christie testified as “just a friend” to amend the heirship to include “David, his posthumous son” as an heir.

Initially Robert Marshall’s estate included $4,000 cash in the bank and a claim against the Pennsylvania Railroad for $10,000 for wrongful death. No other property or assets. By the next summer, it was clear that “it would be almost impossible to recover a case of a suit brought against the Railroad company.” Instead, a settlement of $750 was offered and accepted.

The rest of the files included the Final Account, dated 26 December 1926 and several additional files in the ensuing years to allow my grandmother to use money for the care and support of her children. In November 1930, her twelve year old son died so she had to petition the court for the $70.85 remaining in his account. In 1937, when son Edward reached his majority, there was another file releasing funds to him. Even as late as 1941, Janet had to request funds from the court for care and support of David.

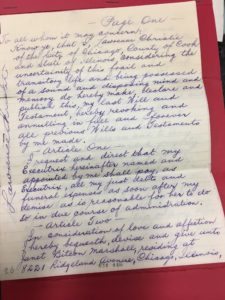

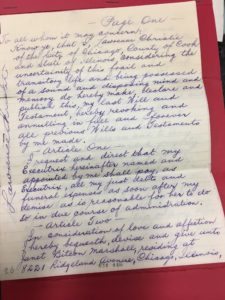

Five years later, Janet was back in court with a handwritten will from Laurence Christie. I found a copy of it in my dad’s dresser after he died. I thought it was the original, but when I opened the files in the archive office, I saw that what I had was a copy. On the back of my copy was a stamp saying it was denied. Laurence Christie wrote the will in 1933, long before he convinced my grandmother to marry him*. It was signed, witnessed and dated, but apparently the court denied it because he married her after the will was executed.

An interview in open court by my grandmother, 9 October 1946, established possible heirs: his widow, two brothers (both in Scotland) and a nephew (in Chicago.) Letters were sent to these individuals by the court with apparently no claims made. Eventually my grandmother received two lots (valued at $100), 75 shares of Stock from Armour & Co. His entire estate was valued at $1500.

I read through all these documents, one by one, and took pictures of most of them with my cell phone (as instructed by the archivist.) It felt strange to handle these documents that ranged in age from 75-90 years and probably hadn’t been touched or viewed for well over 60 years. I don’t imagine anyone will ever look at them again. But they are stored somewhere in the archives and will remain so.

I spent the rest of the day in the Tract Office, looking at records for the house at 8221 S. Ridgeland in Chicago. My grandmother lived in it from 1933 until 1940 and again, in 1946 after Laurence died. I hoped that my grandfather’s business built the house, but I’m guessing that is not true. The owner at the time of building was Buchanan & Norton. In 1928 it was quit claimed to Laurence Christie and then sold to Robert Stewart. In 1929, Laurence quit claimed it to my grandmother and in 1934, Robert Stewart quit claimed it to her. (Anyone want to explain that?) In 1935, my grandmother took out a mortgage on the home. In 1948, Janet quit claimed it to a friend and he quit claimed it back to her the same day. Someone in the office told me that was probably an easy way to have her name changed on the record. She gave it to the friend as Janet Marshall and accepted it back as Janet Christie.

My parents lived in the house from 1947 until 1952, while my grandmother was in California caring for her sister, Martha (for 6-1/2 years.)

In August 1951, my mother gave her 54-year old Ridgeland neighbor a ride to LaGrange to visit her mother. They must have picked up the woman’s mother and were heading elsewhere when my mom ran a stop sign at the intersection of 55th and Wolf. The neighbor and her mother were both killed; my mother (expecting my brother Larry) and David (2) were taken to Wesley Hospital in the city. The other car carried two women and five children, all taken to MacNeal Hospital in Berwyn.

I first heard this story when I was in my late teens. When I was researching at the Chicago History Museum a few weeks ago, an article popped on the screen with the name Eldora Marshall in the middle of it. I freaked a bit–that is not exactly a common name. And then read the article about my mother’s accident.

Apparently the neighbor who lost his wife was less-than-gracious in the months that followed. Larry was born in December and in May my folks moved away and Gramma sold the house. When she returned home from California in 1953 (my birth year) she moved into an English basement apartment at 89th and Bishop, the only “Gramma’s house” any of us remember. She lived there until 1970, when she went to live with Aunt Jean & Uncle Kas.

If you’ve stuck with me this long, my apologies. My friend always says “long story short” and I think this was a short story made long. I love the details, but I understand if others don’t. I’m also not sure how my grandmother would feel about this. She was a very private person so I don’t think she would necessarily applaud my curiosity. In fact, I think I may get a scolding when I meet her in heaven!

* Laurence’s will used a lot of similar phrases but added “In consideration of love and affection” just prior to bequeathing Gramma with all his possessions. He also seemed to be writing all others out of his will, allowing at most that anyone claiming heirship be given no more than one dollar.

One more New Zealand story:

One more New Zealand story: A few days ago, James found not one but two black lambs, a boy and a girl, that had been born during the early morning hours. Anne skyped me when they all went out to meet the lambs, a call I took sitting outdoors at a nice restaurant in Geneva, having dinner with a friend. It was a short, but fun call as I shared in the excitement. I got to watch Charlee hold one of the lambs (briefly).

A few days ago, James found not one but two black lambs, a boy and a girl, that had been born during the early morning hours. Anne skyped me when they all went out to meet the lambs, a call I took sitting outdoors at a nice restaurant in Geneva, having dinner with a friend. It was a short, but fun call as I shared in the excitement. I got to watch Charlee hold one of the lambs (briefly).

I sat down at a table in the Archives office with a mix of excitement and trepidation. There were three files in front of me: two thick (folded) files each labelled “Robert Marshall” and one flat, fairly thin file labelled “Laurence Christie.”

I sat down at a table in the Archives office with a mix of excitement and trepidation. There were three files in front of me: two thick (folded) files each labelled “Robert Marshall” and one flat, fairly thin file labelled “Laurence Christie.”

With Lizi moving back home, I organized the closet in her room to compactly hold–and organiez–her clothes and my (non-sewing) hobbies.

With Lizi moving back home, I organized the closet in her room to compactly hold–and organiez–her clothes and my (non-sewing) hobbies. I needed to cram a lot of books and files into a small space. Back to Ikea (several times) to pick up pieces of the Algot system and figure out how to use the space well. I finished our new, organized closet by the end of August.

I needed to cram a lot of books and files into a small space. Back to Ikea (several times) to pick up pieces of the Algot system and figure out how to use the space well. I finished our new, organized closet by the end of August.

Last, but certainly not least, we were able to get our garage organized by the end of September. Another Kallax system and more bins, a massive workbench and pegboard, and numerous shelves. Our bikes are stored up high on pulleys for easy access and sports bins hold the balls, discs, and skates. A rail system holds gardening tools, etc. Plus we either stored (garage attic) or threw out the rest of our junk.

Last, but certainly not least, we were able to get our garage organized by the end of September. Another Kallax system and more bins, a massive workbench and pegboard, and numerous shelves. Our bikes are stored up high on pulleys for easy access and sports bins hold the balls, discs, and skates. A rail system holds gardening tools, etc. Plus we either stored (garage attic) or threw out the rest of our junk.

We bought a house in the burbs!

We bought a house in the burbs!

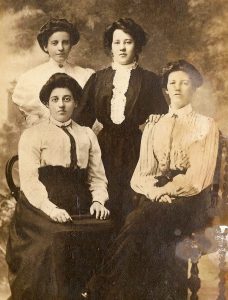

I love this picture of four sisters: Jennie, Maggie, Martha and Lizzie. They were born to James and Agnes (Gray) Bitcon during a ten-year span of years from 1881 to 1891 in Dumbarton, Scotland. By 1897, they were fatherless, with limited resources and no social security. They worked together to make ends meet. All but one would eventually emigrate to America to seek a better life.

I love this picture of four sisters: Jennie, Maggie, Martha and Lizzie. They were born to James and Agnes (Gray) Bitcon during a ten-year span of years from 1881 to 1891 in Dumbarton, Scotland. By 1897, they were fatherless, with limited resources and no social security. They worked together to make ends meet. All but one would eventually emigrate to America to seek a better life.

Last Sunday night, James, Anne and I hiked to the glow worm cave with a group of campers. I’ve done this hike two times before and knew it was a short though strenuous hike. It required climbing up and down a steep trail, sometimes scrambling over fallen trees, wading through a cold stream to the bottom of a ravine where a waterfall met sky and darkness, and the walls of the “cave” were lit up with glow worms. I also knew that James would take good care of Anne during the hike.

Last Sunday night, James, Anne and I hiked to the glow worm cave with a group of campers. I’ve done this hike two times before and knew it was a short though strenuous hike. It required climbing up and down a steep trail, sometimes scrambling over fallen trees, wading through a cold stream to the bottom of a ravine where a waterfall met sky and darkness, and the walls of the “cave” were lit up with glow worms. I also knew that James would take good care of Anne during the hike.

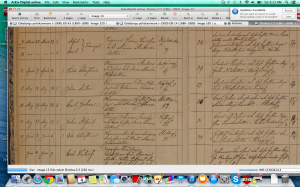

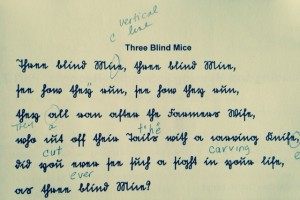

That afternoon and the next day were spent in lectures about burial practices and graveyards (I had a hard time staying awake through that one,) finding living relatives, military records (I do have a couple of soldier ancestors and had already found my way around some of these records,) and two sessions on understanding Swedish written in Gothic handwriting. It’s fairly easy to use the Swedish records for the basic facts of an ancestor’s life, but interspersed in the records are all kinds of remarks, written in Swedish in this old style of writing. Many S’s look like f’s, which is true in English as well, but I learned that most a’s aren’t closed so that they look like u’s; e’s look like n’s, h’s can look like g’s and so on. The above example is a gothic font (so much more uniform than normal handwriting) of Three Blind Mice in English. Look closely to see how challenging reading it can be, and then imagine the variations of handwriting, the extra flourishes, and the Swedish language.

That afternoon and the next day were spent in lectures about burial practices and graveyards (I had a hard time staying awake through that one,) finding living relatives, military records (I do have a couple of soldier ancestors and had already found my way around some of these records,) and two sessions on understanding Swedish written in Gothic handwriting. It’s fairly easy to use the Swedish records for the basic facts of an ancestor’s life, but interspersed in the records are all kinds of remarks, written in Swedish in this old style of writing. Many S’s look like f’s, which is true in English as well, but I learned that most a’s aren’t closed so that they look like u’s; e’s look like n’s, h’s can look like g’s and so on. The above example is a gothic font (so much more uniform than normal handwriting) of Three Blind Mice in English. Look closely to see how challenging reading it can be, and then imagine the variations of handwriting, the extra flourishes, and the Swedish language.